In 1967, a 24-year-old PhD student detected a mysterious signal in the sky.

They were pulsars, rapidly spinning neutron stars.

A major discovery later rewarded with a Nobel

Prize… that she never received.

The story of Jocelyn Bell Burnell perfectly illustrates the Matilda

Effect, the invisibilization of women scientists.

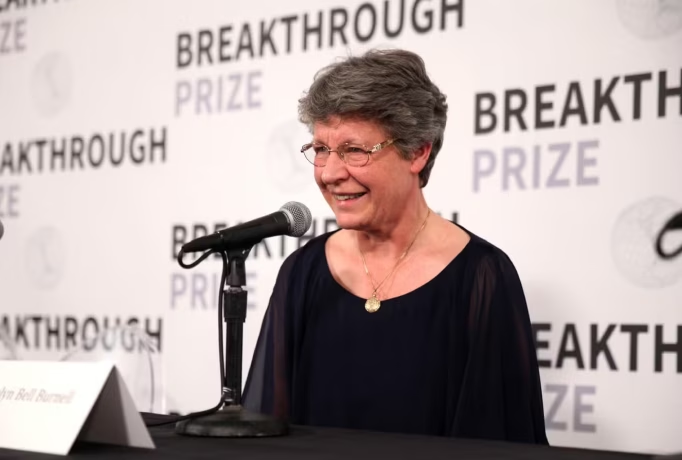

Photograph of Jocelyn Bell Burnell at the Cambridge Radio Astronomy Laboratory

A brilliant student facing the universe

While completing her doctorate at the University of Cambridge, Jocelyn

Bell Burnell spent hours analyzing miles of radio telescope charts she had helped build.

That’s

when she noticed a regular, precise signal — neither a normal star nor a technical error.

It

was a neutron star rotating at incredible speed: a pulsar.

Her intuition and scientific rigor

led to one of the most important discoveries in modern astrophysics.

When recognition slips away

In 1974, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Antony Hewish and

Martin Ryle, her supervisors, for the discovery of pulsars.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell’s name wasn’t

even mentioned.

This injustice became a symbol of structural sexism in science.

“It would be dishonest to say I wasn’t disappointed. But I knew how things worked back then.”

“The stars don’t care who discovers them.” — Jocelyn Bell Burnell

A fight for future generations

Far from bitterness, Jocelyn Bell Burnell dedicated her career to

encouraging young women to pursue science.

In 2018, after receiving the Breakthrough Prize, she

donated the entire reward to fund scholarships for women and minorities in physics.

“If my story can inspire a young woman to believe in her place in science, then that’s a victory.”

By Valentin DEROO, MMI student

Published on 20/10/2025